I just read William Finnegan’s New Yorker profile of famed Arizona Sheriff Joe Arpaio, whose idea of effective law enforcement is to deploy a large, heavily armed, flak-jacketed squadron in order to arrest three undocumented cleaning ladies, without notifying the local police in Mesa, Arizona — an arrogant oversight that could have sparked a friendly-fire shootout in a populous American city. Finnegan does a calm, masterly job, portraying Arpaio as a man who would be pitiful if he weren’t so powerful; a man who, at the end of the day, cares more about befriending celebrities and chasing publicity than really fighting crime.

I just read William Finnegan’s New Yorker profile of famed Arizona Sheriff Joe Arpaio, whose idea of effective law enforcement is to deploy a large, heavily armed, flak-jacketed squadron in order to arrest three undocumented cleaning ladies, without notifying the local police in Mesa, Arizona — an arrogant oversight that could have sparked a friendly-fire shootout in a populous American city. Finnegan does a calm, masterly job, portraying Arpaio as a man who would be pitiful if he weren’t so powerful; a man who, at the end of the day, cares more about befriending celebrities and chasing publicity than really fighting crime.

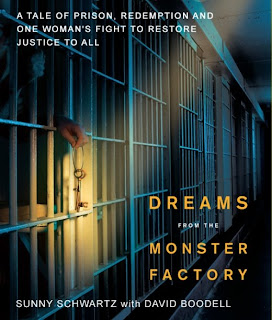

Let’s contrast that with Sunny Schwartz. To make a long story short, Sunny is practically family to me, and she’s written an absorbing page-turner of a book on her innovations in the San Francisco prison system. Far from a dry public policy text, it’s an intimate, self-questioning and nondogmatic, often painful memoir, one of the most effective, unforced meldings of the personal and political I’ve yet to come across. (She discusses the book in a short video on her Amazon page.)

In his New Yorker story, Finnegan mentions Sheriff Arpaio’s curtailing of prisoners’ TV privileges. I had to laugh. Sunny took away their TV too, but to totally different and far more productive ends. And that’s the core contribution of Dreams from the Monster Factory: it upends the soft-on-crime/tough-on-crime dichotomy and takes a long, hard look at getting results. What can be more tough than putting violent offenders in the same room with crime victims and forcing them to confront the consequences of their actions? Encouraging them to get educated and turn their lives around, so that their communities can live in peace? Ultimately, as Sunny shows, the best way to shake up inmates is to humanize them, not dehumanize them. Dehumanization is what they expect. It ensures continuation of the same patterns. Worse, it teaches them to become even more ruthless and deceitful.

Here’s the rub: Sunny’s approach, as she’s the first to admit, isn’t successful 100 percent of the time. (What is?) It also requires grueling, risky, nonstop work, and a willingness on the part of public servants to put themselves on the line. People like her are a rare, indispensable asset to our country.

Comments are closed.